I Left My Heart In…

How well I remember the first time I travelled along the Amalfi Coast. I was in my late teens and could barely bring myself to look out the window of the car, not just because of the vertiginous hairpin bends and risk-taking cars and buses, but also because the sheer, limestone cliffs all the way along the coast dropped straight into the sea.

My father and sister were braver. She sat up front with him while he negotiated with (and swore at) the oncoming traffic while she kept her head down and studied the map, trying to make sense of signs which pointed in all directions (there were no Google Maps or GPS in those days).

Yet I remember I being spellbound by the majestic beauty of this coastline with its vivid blue sea and hazy mirage of islands and peninsulas beyond; and how awestruck I was by the industriousness and tenacity of the people who clung to this coastline and managed to make a living from it.

Decades later, I’m still spellbound.

On my first study trip as part of the Master’s degree I’m doing at UNISG in Pollenzo, northern Italy, I was fortunate to re-visit this magnificent part of Italy with a group of students from my class.

We spent the first few days in and around Napoli, checking out La Notizia pizzeria on the first afternoon, a member of the local Slow Food Condotta, where the owner Enzo Coccia told us about “pizza Napoletana” and how it tells the story of Napoli.

“The word pizza comes from the Latin focacius, a flat bread known to the Romans, and originated in the mid 18th century amongst the poor of Napoli when the tomato had begun to be extensively used. Essentially it’s a flat disc with tomatoes on top.

“But a true pizza Napoletana must be made with the right flour (from il Molino Caputo di Napoli;), the right water, salt and yeast and be made by hand. And then you must use the right tomatoes, grown around Mt Vesuvius (pomodorino del piennolo del Vesuvio, Casa Barone di Somma) and the right extra virgin oil (Le Tore di Massalubrense).”

“The dough must be given at least 12 – 14 hours to rise. Some people are pizza killers (hmm…is he referring to Jamie Oliver?) because they they only give it half an hour to rise. It should be thin in the middle and 1.5cm -2cm around the perimeter. The side should be slightly burnt and the tomato sauce spread lightly over the top.

“We call it Il Sole nel Piatto – the sun on a plate.”

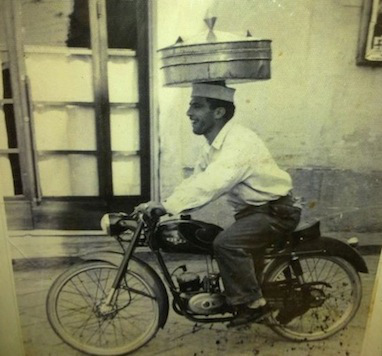

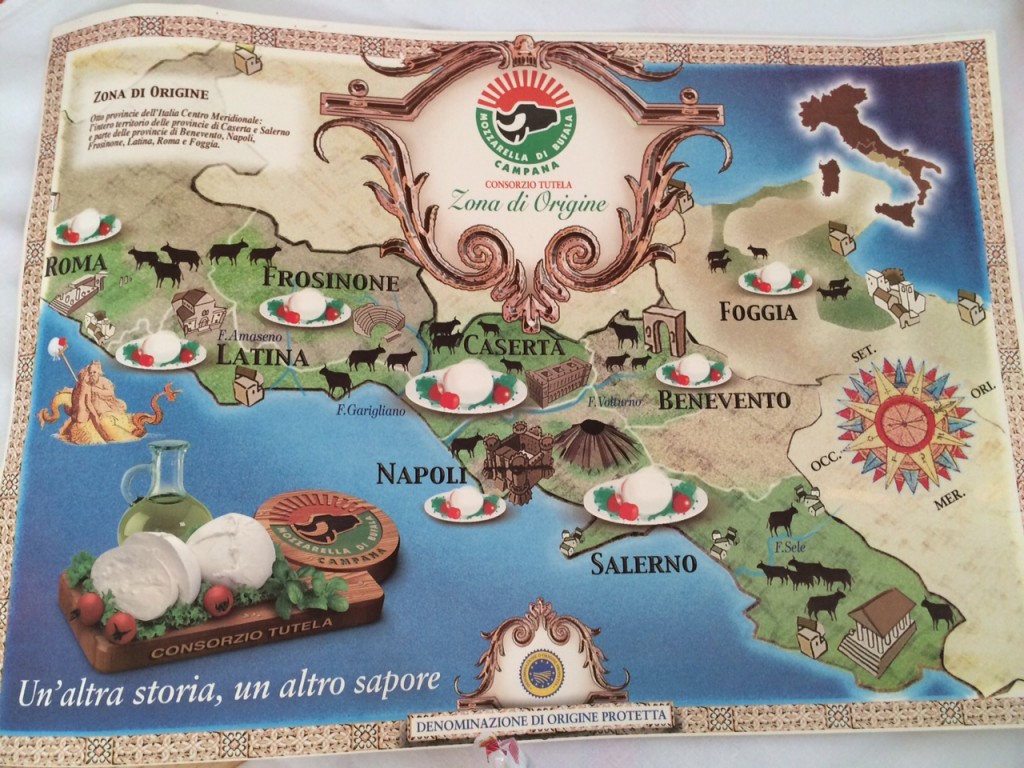

Over the next few days, we visited a number of outstanding Slow Food local producers in the Campnia Felix region: a buffalo mozzarella factory in Caserta, north of Napoli, called Agrozootecnica Marchesa and a nearby buffalo farm in the heart of the terra dei fuochi country, and the Magliulo winery at Aversa where the harvesting of asprinio grapes is yet another manifestation of “heroic agriculture.”

The following day at Gragnano, a town renowned for some of the best dried pasta in Italy, we visited Pastificio dei Campi, an outstanding of example of bronze-extruded artisanal-style pasta made with the very best quality durum wheat in a state-of- the art factory; and then to an artichoke farm (“carciofi violetto di Castellammare”), where the mother artichoke wears a terracotta hat (“pignatelli”) to protect the outer leaves.

Yet I remember I being spellbound by the majestic beauty of this coastline with its vivid blue sea and hazy mirage of islands and peninsulas beyond; and how awestruck I was by the industriousness and tenacity of the people who clung to this coastline and managed to make a living from it.

Decades later, I’m still spellbound.

On my first study trip as part of the Master’s degree I’m doing at UNISG in Pollenzo, northern Italy, I was fortunate to re-visit this magnificent part of Italy with a group of students from my class.

We spent the first few days in and around Napoli, checking out La Notizia pizzeria on the first afternoon, a member of the local Slow Food Condotta, where the owner Enzo Coccia told us about “pizza Napoletana” and how it tells the story of Napoli.

“The word pizza comes from the Latin focacius, a flat bread known to the Romans, and originated in the mid 18th century amongst the poor of Napoli when the tomato had begun to be extensively used. Essentially it’s a flat disc with tomatoes on top.

“But a true pizza Napoletana must be made with the right flour (from il Molino Caputo di Napoli;), the right water, salt and yeast and be made by hand. And then you must use the right tomatoes, grown around Mt Vesuvius (pomodorino del piennolo del Vesuvio, Casa Barone di Somma) and the right extra virgin oil (Le Tore di Massalubrense).”

“The dough must be given at least 12 – 14 hours to rise. Some people are pizza killers (hmm…is he referring to Jamie Oliver?) because they they only give it half an hour to rise. It should be thin in the middle and 1.5cm -2cm around the perimeter. The side should be slightly burnt and the tomato sauce spread lightly over the top.

“We call it Il Sole nel Piatto – the sun on a plate.”

Over the next few days, we visited a number of outstanding Slow Food local producers in the Campnia Felix region: a buffalo mozzarella factory in Caserta, north of Napoli, called Agrozootecnica Marchesa and a nearby buffalo farm in the heart of the terra dei fuochi country, and the Magliulo winery at Aversa where the harvesting of asprinio grapes is yet another manifestation of “heroic agriculture.”

The following day at Gragnano, a town renowned for some of the best dried pasta in Italy, we visited Pastificio dei Campi, an outstanding of example of bronze-extruded artisanal-style pasta made with the very best quality durum wheat in a state-of- the art factory; and then to an artichoke farm (“carciofi violetto di Castellammare”), where the mother artichoke wears a terracotta hat (“pignatelli”) to protect the outer leaves.

The next day it was up the steep winding hills to Agerola, where swirling clouds and mist cloak the rugged mountain landscape. You don’t have to wait long for them to clear and reveal swoon-inducing views down to Amalfi and over the Gulf of Salerno.

Here we visited Salumificio Ruocco and saw how their pancetta rotolata, prosciutto and salami are processed. Later on, at Azienda Agricola Milo Raffaele, we watched as Giuseppina Milo and various members of her family made cow milk mozzarella by hand, and then sat down to a very generous lunch prepared by the family and friends.

But it was when we arrived at the Marisa Cuomo Winery in Furore back down on the coast that I fell in love with this part of Italy all over again.

Standing on the busy roadway opposite the Cantina, looking down towards the sea over the steep terraces, I saw how the roots of the vines actually grow out of the stone walls, and listened as Andrea Ferraoli told us the extraordinary history of the Co-operative he established four years ago to make best use of the tiny scattered vineyards around Furore.

“People here have always tried to find new ways to cultivate and improve the land,” he said. “I am not an agronomist or an oenologist, but I’ve had the good luck to come from a family of peasants who have been growing and making wine here since the sixteenth century – their nickname was Bacco.”

“It’s an extreme form of viticulture here where you have to be ingenious to cultivate grapes. It’s because of the land, which is not volcanic but was originally part of the sea, plus the micro-climate here, that our wines are different.”

And it’s that very landscape – and micro-climate – that people from all over the world fall in love with along this coastline and that give these wines a ranking of No.15 in the list of best of wines in the world. American wine connoisseur Robert Parker is due to visit mid-May.

“For such a small estate, we are getting great results,” he added.

Our all too brief trip to Camapnia Felix ended with a visit to Cetara where we learnt about the extraordinary colatura tradizionale alice di Cetara at Nettuno’s, a type of fish sauce made from local anchovies, similar to the ancient Roman “garum”, which is used to flavour pasta dishes, vegetables and bread.

“Just mix two tablespoons of colatura together with two tablespoons extra virgin olive and some freshly chopped parsley and garlic. Let it rest a while, then cook some good spaghetti from Gragnano without salt , drain it and toss the hot pasta with the cream of colatura. So simple and tasty! It’s also good on steamed fish, potatoes and on brushetta. Garnish with chill, if you like,” said Giulio Nettuno of Nettuno Colatura.

But my very favourite part of the trip was the last half hour, when we soaked up the sun on the pebbly beach of Cetara, and basked in the warmth of the south.

I never wanted to leave.

The next day it was up the steep winding hills to Agerola, where swirling clouds and mist cloak the rugged mountain landscape. You don’t have to wait long for them to clear and reveal swoon-inducing views down to Amalfi and over the Gulf of Salerno.

Here we visited Salumificio Ruocco and saw how their pancetta rotolata, prosciutto and salami are processed. Later on, at Azienda Agricola Milo Raffaele, we watched as Giuseppina Milo and various members of her family made cow milk mozzarella by hand, and then sat down to a very generous lunch prepared by the family and friends.

But it was when we arrived at the Marisa Cuomo Winery in Furore back down on the coast that I fell in love with this part of Italy all over again.

Standing on the busy roadway opposite the Cantina, looking down towards the sea over the steep terraces, I saw how the roots of the vines actually grow out of the stone walls, and listened as Andrea Ferraoli told us the extraordinary history of the Co-operative he established four years ago to make best use of the tiny scattered vineyards around Furore.

“People here have always tried to find new ways to cultivate and improve the land,” he said. “I am not an agronomist or an oenologist, but I’ve had the good luck to come from a family of peasants who have been growing and making wine here since the sixteenth century – their nickname was Bacco.”

“It’s an extreme form of viticulture here where you have to be ingenious to cultivate grapes. It’s because of the land, which is not volcanic but was originally part of the sea, plus the micro-climate here, that our wines are different.”

And it’s that very landscape – and micro-climate – that people from all over the world fall in love with along this coastline and that give these wines a ranking of No.15 in the list of best of wines in the world. American wine connoisseur Robert Parker is due to visit mid-May.

“For such a small estate, we are getting great results,” he added.

Our all too brief trip to Camapnia Felix ended with a visit to Cetara where we learnt about the extraordinary colatura tradizionale alice di Cetara at Nettuno’s, a type of fish sauce made from local anchovies, similar to the ancient Roman “garum”, which is used to flavour pasta dishes, vegetables and bread.

“Just mix two tablespoons of colatura together with two tablespoons extra virgin olive and some freshly chopped parsley and garlic. Let it rest a while, then cook some good spaghetti from Gragnano without salt , drain it and toss the hot pasta with the cream of colatura. So simple and tasty! It’s also good on steamed fish, potatoes and on brushetta. Garnish with chill, if you like,” said Giulio Nettuno of Nettuno Colatura.

But my very favourite part of the trip was the last half hour, when we soaked up the sun on the pebbly beach of Cetara, and basked in the warmth of the south.

I never wanted to leave.

Yet I remember I being spellbound by the majestic beauty of this coastline with its vivid blue sea and hazy mirage of islands and peninsulas beyond; and how awestruck I was by the industriousness and tenacity of the people who clung to this coastline and managed to make a living from it.

Decades later, I’m still spellbound.

On my first study trip as part of the Master’s degree I’m doing at UNISG in Pollenzo, northern Italy, I was fortunate to re-visit this magnificent part of Italy with a group of students from my class.

We spent the first few days in and around Napoli, checking out La Notizia pizzeria on the first afternoon, a member of the local Slow Food Condotta, where the owner Enzo Coccia told us about “pizza Napoletana” and how it tells the story of Napoli.

“The word pizza comes from the Latin focacius, a flat bread known to the Romans, and originated in the mid 18th century amongst the poor of Napoli when the tomato had begun to be extensively used. Essentially it’s a flat disc with tomatoes on top.

“But a true pizza Napoletana must be made with the right flour (from il Molino Caputo di Napoli;), the right water, salt and yeast and be made by hand. And then you must use the right tomatoes, grown around Mt Vesuvius (pomodorino del piennolo del Vesuvio, Casa Barone di Somma) and the right extra virgin oil (Le Tore di Massalubrense).”

“The dough must be given at least 12 – 14 hours to rise. Some people are pizza killers (hmm…is he referring to Jamie Oliver?) because they they only give it half an hour to rise. It should be thin in the middle and 1.5cm -2cm around the perimeter. The side should be slightly burnt and the tomato sauce spread lightly over the top.

“We call it Il Sole nel Piatto – the sun on a plate.”

Over the next few days, we visited a number of outstanding Slow Food local producers in the Campnia Felix region: a buffalo mozzarella factory in Caserta, north of Napoli, called Agrozootecnica Marchesa and a nearby buffalo farm in the heart of the terra dei fuochi country, and the Magliulo winery at Aversa where the harvesting of asprinio grapes is yet another manifestation of “heroic agriculture.”

The following day at Gragnano, a town renowned for some of the best dried pasta in Italy, we visited Pastificio dei Campi, an outstanding of example of bronze-extruded artisanal-style pasta made with the very best quality durum wheat in a state-of- the art factory; and then to an artichoke farm (“carciofi violetto di Castellammare”), where the mother artichoke wears a terracotta hat (“pignatelli”) to protect the outer leaves.

Yet I remember I being spellbound by the majestic beauty of this coastline with its vivid blue sea and hazy mirage of islands and peninsulas beyond; and how awestruck I was by the industriousness and tenacity of the people who clung to this coastline and managed to make a living from it.

Decades later, I’m still spellbound.

On my first study trip as part of the Master’s degree I’m doing at UNISG in Pollenzo, northern Italy, I was fortunate to re-visit this magnificent part of Italy with a group of students from my class.

We spent the first few days in and around Napoli, checking out La Notizia pizzeria on the first afternoon, a member of the local Slow Food Condotta, where the owner Enzo Coccia told us about “pizza Napoletana” and how it tells the story of Napoli.

“The word pizza comes from the Latin focacius, a flat bread known to the Romans, and originated in the mid 18th century amongst the poor of Napoli when the tomato had begun to be extensively used. Essentially it’s a flat disc with tomatoes on top.

“But a true pizza Napoletana must be made with the right flour (from il Molino Caputo di Napoli;), the right water, salt and yeast and be made by hand. And then you must use the right tomatoes, grown around Mt Vesuvius (pomodorino del piennolo del Vesuvio, Casa Barone di Somma) and the right extra virgin oil (Le Tore di Massalubrense).”

“The dough must be given at least 12 – 14 hours to rise. Some people are pizza killers (hmm…is he referring to Jamie Oliver?) because they they only give it half an hour to rise. It should be thin in the middle and 1.5cm -2cm around the perimeter. The side should be slightly burnt and the tomato sauce spread lightly over the top.

“We call it Il Sole nel Piatto – the sun on a plate.”

Over the next few days, we visited a number of outstanding Slow Food local producers in the Campnia Felix region: a buffalo mozzarella factory in Caserta, north of Napoli, called Agrozootecnica Marchesa and a nearby buffalo farm in the heart of the terra dei fuochi country, and the Magliulo winery at Aversa where the harvesting of asprinio grapes is yet another manifestation of “heroic agriculture.”

The following day at Gragnano, a town renowned for some of the best dried pasta in Italy, we visited Pastificio dei Campi, an outstanding of example of bronze-extruded artisanal-style pasta made with the very best quality durum wheat in a state-of- the art factory; and then to an artichoke farm (“carciofi violetto di Castellammare”), where the mother artichoke wears a terracotta hat (“pignatelli”) to protect the outer leaves.

In the carciofi (artichoke) patch with Gennaro the gardener at Castellammare (I’m missing a terracotta hat on my head!)